Un des premiers objets de la discipline, c’est de fixer; elle est un procédé d’anti-nomadisme.

One of the first objects of a discipline is to fix. It is a product of anti-nomadism.

—Michel Foucault, Surveiller et punir, p. 254

Arriving at Edo by boat on the Sumida River, on his way to the kabuki, the scapegrace narrator of Asai Ryōi’s Tōkaidō meishoki (Famous Places along the Tōkaidō; 1661), laments that too many men “have had their souls stolen…by beautiful boys” at the theaters (Elisonas 1994:253-4). Ryōi’s riverine imagery describes the culture of the ukiyo (floating world): confluent yet aimless, channeled yet overflowing barriers, its content a continual mix, constrained only by larger forces such as the flow of time. Illustration and text were often interdependent, and genres intermingled:

Professional rakugo storytelling provided gesaku [playful parodic] fiction with puns and wordplay [and character sketches], ukiyo-e…provided illustrations, and the jōruri puppet theatre and the kabuki male actor theatre, plots and language. (Cross 2004:1)

Consumers and producers intermingled too. They collaborated, sometimes closely, on haikai, books, publications, calligraphy, and artwork, meeting at parties as well as at the theaters, and in restaurants, shops, and brothels.

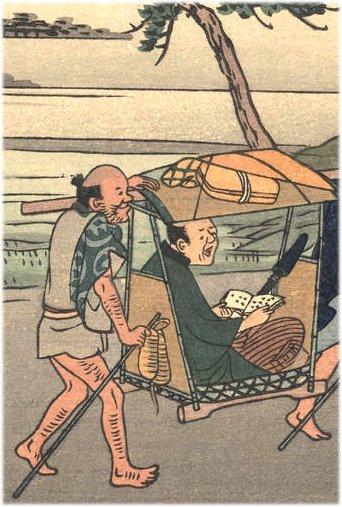

Fig. 1. Fujikawa Tamenobu. Hirasata. c. 1918.

The good-natured but bumbling friends of Tōkaidōchū hizakurige, Kita (left) and Yaji, wreak havoc on their pilgrimage to the Ise shrine. They have hired bearers to carry them across the Banjugawa. Yaji tries to impress them with his local knowledge. Rather than doing so from memory, as would a tsu, he relies on a guidebook. They had been lovers until Kita reached adulthood.

In spite of periodic repression such as the Kansei (1787-93) and Tenpō reforms (1841-43) the uikyo persisted through the end of the Edo period (1603-1868). Jippensha Ikku’s comic road novel, Tōkaidōchū hizakurige (Down the Tōkaidō on foot; 1802) is one of Edo’s most popular works, a best seller with dozens of editions published into the Meiji period (Kornicki 1981:472). A series of woodblock prints depicting scenes from the story was published in the early twentieth century (Fig. 1) and the book remains in print today. Timon Screech wrote that its “run-away success was probably the inspiration for Hokusai’s equally famous print series, The Fifty-three Stages of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi)” (1999:270). Contemporary parodists published their own versions, some of them “arrantly sexual spinoffs” (272). The shōjo (girls’) manga artist Moto Hagio, whose Tōma no shinzō (Thomas’s heart; 1974) is foundational to BL manga, told an interviewer that it was the only book she read from the Japanese classics corner in her elementary school’s library (Thorn 2005).

Bodily coercion

Beginning in the second half of the eighteenth century, as the uikyo produced an outpouring of cultural products, Europe and North America developed new ideas, strategies and technologies to restrict the ability of people and their activities to freely float across boundaries.

Michel Foucault theorized that these changes stemmed in part from the industrializing economy and the Enlightenment’s emphasis on a social contract wherein rights and obligations replaced feudal duties. Liberatory in some aspects, the new systems were repressive in others. Surveillance became emphasized. States needed to know not just where people were and what they did but what they thought. In his 1975 book Surveiller et punir (Discipline and Punish), Foucault elaborated six major rules on which Enlightenment states based what he called a semiotechnic of their power to punish.* All of these involve newly fixed, permanent, relations among crime and punishment. Their effect was to restrict autonomy, discretion and other qualities that depend on movement. The results included,

a tighter grid around the population, better adjusted techniques of identification, capture, information…. an effort to adjust power mechanisms that frame the existence of individuals [with] denser controls…. (93)

He provides accounts of these new rules playing out against real people. One is of a thirteen-year-old boy, Béasse, hauled before a Paris tribunal in the summer of 1840. He was, wrote Foucault, “without home or family” (339-40). To the court, that meant that he was without a place not just to live but as a citizen. Béasse resisted the attempt to normalize his life. To the chief judge’s “You must sleep at home”, the lad responded ironically—insolently, given the power difference between him and the judges—”Do I have a home?”. The questioning continued:

“You are living in perpetual vagabondage.”

“I work to earn my way.”

“What is your state?”, meaning Béasse’s place in society. One can imagine the boy’s pondering that question for a moment, stateless as he was.

“My state…. It’s been a while already since I’ve had a room. I have my day and night states.” He then described what he did each day and night. (340)

Although there was no allegation of criminality or evidence that Béasse could not support himself on his own, however hardscrabble his life may have been, and he testified that he earned a living during his day and night states by distributing flyers, opening doors to theaters, and selling ticket vouchers, he was condemned to two years imprisonment where he would be monitored and taught correct behavior. From multiple states he was reduced to one: criminal.

In Foucault’s conception of the court’s hearing,

All the illegalities that the court saw as offenses, the accused reformulated as the affirmation of a living force: the lack of habitat as vagabondage, the absence of a master as autonomy, lack of work as freedom, the absence of a schedule as a plentitude of days and nights. (340)

A living force, one that could move where it wanted, that had not (yet) been fixed. It threatened this society. “Order is brought into existence from disorder” observed Anthony Uhlmann, and Béasse “appears as an example of disorder, and disorder, its very existence within the society of discipline, of surveillance, presents that society with apprehension in the face of the possibility of its own death” (1999:88).

The semiotechnic of punishment helped bring into being “a new political anatomy” (Foucault 1975, 122), one whose power centered and expressed itself on the body: “The new art of punishment shows well the changing of the punitive semiotechnic by a new politics of the body” (ibid.). The criminal body became “the anchorage point for power manifestation” (67). In this process Foucault identified a new type of knowledge he called power/knowledge (pouvoir-savoir):

It is not the activity of the subject of knowledge that would produce a body of knowledge, useful or refractory to power, but power/knowledge, the processes and struggles that traverse it and thus constitute it, that determines the possible forms and domains of knowledge. (36)

Power/knowledge developed from a way of enabling not just the control of threatening social elements but of enhancing on and via the body the utility of those subjected (Rouse 1994:97). Power/knowledge permitted more effective control by a refinement of bodily coercion that may be as totalizing as it is subtle:

It was a question not of treating the body en masse [but] of exercising upon it a subtle coercion, of assuring a hold upon it at the level of the mechanism itself—movements, gestures, attitudes, rapidity: infinitesimal power on the active body. (Foucault 1975:161)

Foucault developed the idea of the imbrication of body and power, writing in The History of Sexuality and elsewhere that power relations demand examination and seek causation via sexuality (1978, 59). He conjured an image of power fucking the body: “power relations can materially penetrate the body in depth” (1980, 186), “wrapp[ing] the sexual body in its embrace” (1978, 44), “an entire glittering sexual array” to produce truth at “a nearly fabulous price” (1978, 72). One of the consequences is the separation of truth and sex, no longer linked by transmission from one body to another as they were, he said, in Ancient Greece (1978, 61) and were, I think, linked in the Edo period via erotic desire such as iki (an aesthetic; sexual passion) and kōshoku (loving love), described below.

Onnagata and bodily desire

Edo-period Japan controlled its population by prescribing obligations among classes even as it restricted interactions between them, prohibiting almost all external travel, restricting internal travel, promulgating sumptuary laws, holding hostage the families of daimyō (domain lords) to ensure their fealty, regulating the “pleasure” quarters and kabuki, censoring books and art and ferreting out those who violated the polity.

The ukiyo arose independent of the shōgunate. Ukiyo expression was surveilled and censored, but the ukiyo as such may not have been thought of as a demimonde worthy of intervention absent illegality. This would be unlike the physical spaces in Europe and America then where males cruised for sex with one another, which, when identified, became loci of surveillance and arrest.

The ukiyo saw not just the creation of cultural products but of an ethos that valued qualities such as iki, kōshoku and kokkei (humor). This was an ethos not simply more liberal than those of Western cultures at that time but a different way of thinking about things. Takayuki Yokota-Murakami noted that the sexual and aesthetic qualities of iki could be “interrelated without any differentiation”:

That iki involves “two” significative axes, one on the sexual plane, the other on the aesthetic plane is, probably, a vision transparent only for the observer whose language segregates the sexual and the aesthetic on different planes…. (Yokota-Murakami 1999:53)

Iki is considered a combination of the two dimensions, the sexual and the beautiful, only because these two are basic categories of Western criticism. (54)

One of the most valued goals in the ukiyo was to be tsu (a connoisseur), someone who could afford asobi (play) and who took a witty and highly informed attitude toward it via kokkei. But always at a distance. The narrator of Hiraga Gennai’s novel Fūryū Shidōken den (The Story of Gallant Shidōken; 1763) remonstrates with its hapless protagonist, the fifteen-year-old Asanoshin, who had not learned the ways of the world even after having undertaken a world tour that goes spectacularly wrong:

[O]nce you had learned about human passions throughout the world you were to detach yourself from society through the medium of humor [kokkei]…. But instead you became so distracted by worldly attachments and were so carried away by your own emotions that time and again you have found yourself in difficulties…. This loss of judgement is not limited to the irrationality accompanying a person’s craze for courtesans. There is harm in forming too great an attachment to anything. (Jones 1968:236-237)

Gennai’s own kokkei literary style follows his advice, distancing himself as author while creating a texture that adds humor to the narrative via puns, wordplay, irony, and allusions to contemporary and classical works and events. Phonetically, “Asanoshin” means “new dawn” (asa no shin) but the word invokes other meanings, notably the auspicious state event called mitsu no asa (threefold dawn, i.e. New Year’s Day) and Gennai’s guide to male prostitution, Mitsu no asa (1768). Adriana Delprat observes that it refers to his own samurai rank of no shin, which was the lowest of five ranks given to the lower samurai echelons (1985:124). Kokkei style is at the heart of gesaku and other ukiyo works.

Kabuki was at the center of ukiyo space. It is often said to have started in the performances of Okuni on the dry Kamo riverbed in Kyoto. Izumo no Okuni (active 1603-?), a temple dancer, created a review, that, according to Katherine Mezur in a fascinating book about onnagata (female gender role specialists), Beautiful Boys/Outlaw Bodies,

combined revamped folk dances with religious chants, ritual, and prayer gestures from a Buddhist incantation and dance. She crowned this with an irreverent mixture of gender and class acts of costuming, accessories, and movement. (Mezur 2005:54)

From its outset, Okuni’s performances transgressed gender. She created dramatic skits that became early staples of kabuki. In some of these, such as a skit about prostitute buying, she played the character of a male customer with a male actor as a female prostitute (ibid.). Okuni also performed a dance named after the ninth-century courtier Ariwara no Narihira, who was

a famous legendary lover and poet of great beauty, frequently referred to for his mixture of feminine and masculine attributes. Okuni performed her version of Narihira somewhere between male and female, even confounding her audience as to whether she was a man or woman…. (55)

Wakashū (youth; boy) had long been objects of desire. Mezur writes that wakashū kabuki had become well established in Kyoto and Edo by 1617 (64). Restrictions on women performers were enacted in 1608 and 1615, but it wasn’t until 1629, with bans segregating male and female performers, abolishing public performance by women, and restricting and licensing female prostitution (61-2) that all-male kabuki came into being.

Women continued to attend kabuki, and some pursued erotic relationships with actors. Ordered on a pilgrimage in 1714, Lady Ejima, one of the highest officials of the women’s quarters in the shogun’s castle, ditched a meeting with an abbot, heading instead to the Yamamura-za to meet her lover, kabuki star Ikushima Shingorō (1671-1743). News leaked about their party in the theater (Shively 1995:348). Punishments for those involved ranged from banishment to death (ibid. 349). Lady Ejima, her family and entourage were banished to Shinshu (Bach 1995:276); Ikushima and the theater’s manager were banished to the island of Miyake-jima. The Yamamura-za, one of Edo’s four great theaters, was demolished (Shively 1955:349). Timon Screech speculates that a scroll painting c. 1725 by the female artist Yamazaki Joryū (active 1716-35) of a boy kabuki actor could have been commissioned by a woman. He asks if this may be “an example of an all-female production of a sexualized image of a man” (1999:151).

Certain traits of wakashū kabuki actors, such as hair with forelocks or bangs (maegami) and later bōshi (caps) (Mezur 2005:66), and whitened faces with red lips (72), were eroticized in performance. These and other wakashū actor traits including “movement, postures, vocal acts, costumes, wigs [and] makeup” (76) evoked iroke (erotic allure):

It is important to emphasize that the wakashu art was first and foremost a danced seduction. Gestures, postures, costuming, vocal articulation, props: everything was an “erotic” act. (147)

Some of these iroke elements may have originated apart from kabuki “in the wakashu system of erotic codes with its own boy/man erotic points and gender ambiguity” (ibid.) and were subsequently carried over into early kabuki performances of wakashū and onnagata. The distinctive and essential feature of their performance, Mezur says, was “communication of iroke” (35). Central to her thesis of onnagata roles “never [being] performed in imitation of real women” (4) but rather being “a constructed female-likeness” (2) is that onnagata iroke is based on an adolescent male body:

Wakashu onnagata stylized and reconstructed the bishōnen ideal appearance…to achieve the look: the long, slim line and willow-like softness of the ideal wakashu body in every gesture and posture.

Subsequent onnagata gradually stylized these boy erotic codes into onnagata gender acts…. [T]hey also assimilated the wakashu trait of gender ambiguity. Moreover, it seems probable that the early onnagata so thoroughly incorporated the wakashu erotic acts into their onnagata art that onnagata standards of beauty were infused with wakashu sensuality. (72)

Mezur argues that for spectators, then and now, “the presence of male sexual organs underneath the kimono is a requirement for kabuki onnagata performance, because the spectator must be able to imagine a male body beneath the feminine costuming” (25, italics in original).

Onnagata, as other kabuki actors, use kata (stylized forms) in their performance. Kata inhere to performance as a way of, in part, communicating iroke. Onnagata kata have been retained and elaborated throughout kabuki history.

The body in ukiyo was consciously performative and the ukiyo was about worldly things. This worried scholars whose study was the spiritual. Harry Harootunian writes that some kokugakusha (in part, nativist scholars) during Edo argued for a “rescue” of the body from the pleasures of gesaku (1988: 407). They attempted to counteract “the bodily excesses of urban culture” (408) which “privileged the ceaseless activity of body over mind” (38).

Resistance to being fixed

According to Joseph Rouse’s view of Foucault’s thinking, “[p]ower is not possessed by a dominant agent, nor located in that agent’s relations to those dominated, but is instead distributed throughout complex social networks” (1994:106). He quotes Foucault that “‘power is not something that is acquired, seized, or shared, something that one holds on to or allows to slip away’” (105). Rather, in Foucault’s words, it is “‘something that circulates’” and is “‘produced from one moment to the next’” (107). Rouse observes that “[p]ower can thus never be simply present [but rather is reproduced] over time as a sustained power relationship” (ibid., italics in original). These relations can, as Foucault said, “‘support…one another, thus forming a chain or a system’” (107). Rouse invokes Thomas Wartenberg’s idea that power relationships encompass social agents in a diffuse field wherein these agents align themselves into coordinated practices of domination (105), coordinations which may happen independent of agents’ intentions (106).

Power is complicit and by preference hidden. A power relationship, wrote Foucault, is indirect: it “does not act directly and immediately on others. Instead it acts upon their actions….acting upon…subjects by virtue of their acting or being capable of action” (1982:789). One of its geniuses is that people act on its behalf against their own interests, a more efficient method of control of subjects than the naked deployment of force. Foucault makes this point more than once in Surveiller et punir, here quoting from a 1767 book by influential penal reform advocate Joseph-Michel-Antoine Servan:

‘A stupid despot can constrain slaves with iron chains, but a true politician binds them even more tightly with the chain of their own ideas…’ (1975:122)

In Europe power militated against people’s ability to be aware of, hence resist, its often subtle, infinitesimal, totalizing hold on the body’s movements, gestures, attitudes. In Edo Japan people in the ukiyo with the resources and inclination to do so consciously developed and cultivated bodily gestures and movement, attitudes, conduct and dress in pursuit of goals, often erotic, of self. Gennai’s narrator tries to teach Asanoshin what kokkei is and why it need be pursued if one is to become tsu. Onnagata kata were a way of an actor’s asserting erotic power via his body. Iki and kōshoku were major themes of floating world works. Erotic desire underlies many of best-selling author Ihara Saikaku’s novels and is overt in the titles of three: Kōshoku ichidai otoko (The Man Who Loved Love; 1682), Kōshoku gonin onna (Five Women Who Loved Love; 1686) and Kōshoku ichidai onna (Life of an Amorous Woman; 1686).

This cultivation was highly valued. It was sought after, studied, worked at, and performed whether as a gesakusha (gesaku writer / artist), an onnagata, a client socializing with actors in a kabuki teahouse or visiting a licensed female prostitution district such as the Yoshiwara or the far more numerous unlicensed brothels, male and female. Its failure is depicted in a woodblock print by Fujikawa Tamenobu where Jippensha Ikku’s character Yaji, though very likeable, fails as utterly as Asanoshin to be tsu. (Fig. 2) So highly valued was this cultivation that it may have helped forestall the ability of expressions of power reflecting other power relationships to take hold on the body.

Onnagata kata and the many other elements of erotic style helped form an ethos unique to ukiyo. This ethos comprehended a nexus between the all-male kabuki and nanshoku (male-male love), the latter going back to the beginnings of Japanese literature and popular in the ukiyo (less so toward the mid-nineteenth century [Pflugfelder 1999:95-6]). In Foucauldian terms, these elements were agents in power fields aligned in sustained coordinations over time and space to link kabuki and nanshoku. These coordinations and this linkage helped the ukiyo to counter agents of power incursions, whether by the disciplines of the shōgunate, the writings of the kokugakusha, the values of the Western Enlightenment (erotic uikyo-e on reaching London was burned), or by entropy.

The object of “fixer” in the epigraph above is “la population flotante” (floating population). Foucult was referring to groups of people, some criminal, roaming the countryside, their existence threatening newly formed lines of property and propriety. In Edo-period Japan it was ideas, cultural products that were able to roam across genres and classes. It took a revolution sparked by an armed intervention by the United States seeking fuel for its industrial revolution and nascent gilded age to end the ukiyo. Until then, the ukiyo’s ethos, its mixing of genres, the determination and creativity of its participants and the very many products that they produced, helped it to persist, to continually evolve, to move, to sidestep control, that is, to float, and thus to prevent it from being fixed by those outside its ambit.

____________________

*To summarize Foucault’s rules of the Enlightenment states’ semiotechnic of power-punishment: Penalties must be fixed; the proximity between the penalty and the crime must be fixed; punishment must be fixed around only one idea, that of maximum effect; the pain of punishment must be fixed in the convicted person’s mind in order to prevent recidivism; there must be certainty (fixity) among judges and the public as to what is and is not a crime so to encourage law-abiding conduct as well as to prevent impunity. (Foucault 1975, 112-18)

Works cited

Bach, Faith. “Breaking the Kabuki Actors’ Barriers: 1868-1900″, Asian Theatre Journal, vol. 12, no. 2 (Autumn, 1995):264-79.

Cross, Barbara. “Representing Performance in Japanese Fiction: Shikitei Sanba (1776-1822)”, SOAS Literary Review, 2004(Autumn).

Delprat, Adriana. Forms of Dissent in the Gesaku Literature of Hiraga Gennai (1728-1780). Ph.D. thesis, Princeton U, 1985.

Elisonas, Jurgis. “Notorious Places: A Brief Excursion into the Narrative Topography of Early Edo” in James L. McClain, John M. Merriman and Ugawa Kaoru, eds., 253-91. Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era. Ithaca, New York: Cornell U P, 1994.

Foucault, Michel. Surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison. Paris: Gallimard, 1975. My translation. (Translated by Alan Sheridan as Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon: 1977.)

——. The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon, 1978.

——. “The History of Sexuality”, interview with Lucette Finas (trans. Leo Marshall) in Colin Gordon, ed., 183-93. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

——. “The Subject and Power”, Critical Inquiry, vol. 8, no. 4 (Summer, 1982):777-95.

Fujikawa Tamenobu. (藤川 為信). Hirasata. Woodblock print, c. 1918.

Harootunian, Harry. Things Seen and Unseen: Discourse and Ideology in Tokugawa Nativism. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1988.

Jones, Stanleigh Hopkins, Jr. Scholar, Scientist, Popular Author: Hiraga Gennai, 1728-1780. Ph.D. thesis, Columbia U, 1968.

Kornicki, Peter F. “The Survival of Tokugawa Fiction in the Meiji Period”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, vol. 41, no. 2 (Dec., 1981):461-82.

Mezur, Katherine. Beautiful Boys / Outlaw Bodies: Devising Kabuki Female-Likeness. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Pflugfelder, Gregory. Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950. Berkeley, CA: U of Calif. P, 1999.

Rouse, Joseph. “Power/Knowledge” in The Cambridge Companion to Foucault, ed. Gary Gutting, 92-114. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U P, 1994.

Screech, Timon. Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan, 1700-1820. Honolulu: U of Hawai’i P, 1999.

Shively, Donald. “Bakufu versus Kabuki”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, vol. 18, no. 3/4 (Dec., 1955):326-56.

Thorn, Matt. “The Moto Hagio Interview”, The Comics Journal 269 (July/August), 2005. <http://matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/hagio_interview.php> Accessed 7 Feb. 2012.

Uhlmann, Anthony. Beckett and Poststructuralism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U P, 1999.

Yokota-Murakami, Takayuki. Don Juan East/West: on the Problematics of Comparative Literature. Albany, NY: State U of New York P, 1998.